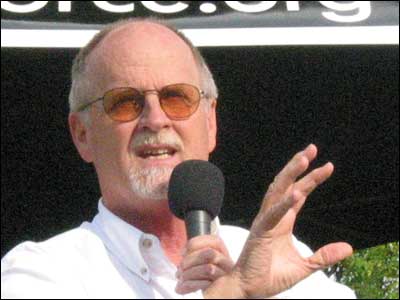

Rev. Mel White penned the life stories and speeches of conservative Christian superstars like Pat Robertson. His religious leaders publicly and vehemently condemned gays and lesbians, and White tried to overcome his homosexuality with exorcisms and electric shock therapy. In 1993, White came out as a gay man and denounced the politics of hate in the evangelical church. Now, 15 years and two books later, White spearheads Soulforce, an organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender acceptance in religious communities.

Here, White discusses the latent power of the Religious Right in the forthcoming presidential election, his antipathy toward civil marriage, and the rationale behind the Religious Right’s homophobia.

Interviewer: Anja Tranovich

Interviewee: Rev. Mel White

What prompted you to come out after many years of marriage and trying to lead a heterosexual life?

I don’t ever remember making the decision to come out. After all the years of marriage, therapies, and counseling to overcome the demon, I finally sliced my wrists. Driving back from the hospital, my wife said, “You know, you are a gay man.”

We separated, and slowly I started learning about my sexuality. First, I learned to accept it, then to celebrate it, and finally, to share it, as the truth dawned on me that it is a gift from God, just like heterosexuality is a gift from God.

In 1993, I had my public coming-out. Since the Religious Right that I had worked for for so long refused to listen to me, I wrote my book, Stranger at the Gate: To Be Gay and Christian in America. I needed them to hear me, and the book was a national coming-out.

I know you were raised as an evangelical Christian. Do you still consider yourself one? What does that label mean for you?

I consider myself an evangelical, but I don’t advertise it widely.

I am an evangelical, meaning “good news recipient and bearer” — that God loves humankind. I’m trying to both appropriate good news for myself in my own life, follow Jesus as best I can, and share the good news.

You’ve said in the past that gays are the top villain right now for the Christian Right. Do you still think that’s still accurate?

I think the Christian Right is widening its target to include illegal immigration and abortion doctors in terms of the amount of vitriol, but homosexuals still take the biggest beating. We [at Soulforce] monitor the Religious Right media. We’ve got filing cabinets filled with data. Much of this is a caricaturizing of homosexuals, condemning and demonizing.

Why have they targeted homosexuality? Where does that impulse come from? Is it really rooted in religious conviction and a literal reading of the Bible?

It is very important that we acknowledge they are sincere in their fears about homophobia — it is dangerous to see them as insincere. They are true believers.

They think if we break out of the sexual roles we were meant to play from the beginning — if a man takes on the role of a woman, which is how they view homosexuality — and the country accepts it, then the country is accepting a grave sin, and God can no longer bless the country.

What is your response to those sentiments?

Empirical and biblical data don’t support the position that homosexuality is a sickness or [a] sin. The Religious Right has to ignore all the data to make [a] case against us, and misuses the Bible to condemn us. We must remember that the Bible has been used throughout the centuries to support intolerance, and now it is being used again to support homophobia.

You spent some time a few years ago talking about homosexuality with Fred Phelps of “God hates fags” fame. What was that like? Was it possible to have a dialogue?

Fred Phelps is a former [American Civil Liberties Union] ACLU lawyer. He has a doctorate. He reads in Greek and in Hebrew. He has a massive theological library.

His favorite preacher is Jonathan Edwards, and Jonathan Edwards dangled sinners above fiery hell to awaken them to their “lostness.” He believes anyone who accepts his or her homosexuality is lost [and] needs to be awakened. We spoke quietly and calmly for about two hours on his views.

He is a Calvinist, and his sermonizing uses fear to drive people into the arms of God. He looks like a nutcase, but he really isn’t. He has a rationale for what he is doing, and that’s what is most frightening. He is not only a sincere believer, he is following a historic tradition.

You are about to celebrate the 10th anniversary of your organization, Soulforce, and you first spoke out publicly against Christian homophobia 15 years ago. What has changed since you started doing this work?

Well, now we are having internecine wars not seen 15 years ago over gay issues. Large churches are splitting apart so that they don’t have to accept gays. Famous pastors and preachers are getting kicked out for supporting [ordination] of gay leaders.

There is a growing mass of allies, gay and straight alike, fighting the battle. It’s true that the media has changed a lot, but there is a strong backlash. Now people have discussions about whether clergy should deny membership to homosexuals. It is absolutely heresy to keep people out of Christ’s church!

There is a terrible threat to fall backwards. We could easily be completely taken over by these well-meaning fundamentalists.

Is the extension of civil marriage rights important to you — would you like to legally wed your partner?

Absolutely. We have been together 27 years now; I am looking Father Time in the eye. If we had equal rights, he would get my social security. As [it] is now, he will lose tens of thousands [of] dollars a year, those kinds of things.

We can’t have a will that in any way looks like marriage, we can’t do our income taxes together, we double pay. It’s just bizarre that we don’t have those rights. It’s not about religion; it is about civil rights. We are not arguing for civil unions, it has to be called “marriage” to have equal laws.

We have been married in the eyes of each other and in the eyes of our families and in the eyes of God. We have marriage; we just don’t have the civil rights to go with [it].

Do you have a take on the upcoming presidential elections? Are we entering into a new era where the Religious Right doesn’t have as much political power?

I think the Religious Right doesn’t have a political candidate. Therefore, they are simply waiting. Their organizations are still very much in place, accumulating funds and members and power. They don’t have a candidate, and they are divided over McCain. But they are not dead, just latent, waiting.

And evangelical work has changed somewhat. It has broadened. They are more interested in issues of the environment and the earth, poverty, HIV-AIDS. But among even progressive evangelicals, none have come out for gay marriage — Jim Wallace, Tony Campolo — none of them is our ally.

I am offended when Christians suggest gays are unworthy of marriage and therefore second-class. It creates an environment where gays are killing themselves when even progressive Christians say your marriage isn’t worthy, is sinful; in other words you are sinful, unworthy.

I’m really offended when people think they are taking a giant step forward when they call for civil unions and refuse to call them by their right name. It is true that some are calling for civil unions, but when they say our relationship is not worthy of marriage, it is demeaning. I’m being demeaned by my friends as well as [by] my enemies.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content

Activist Lupe Anguiano reflects on a life spent fighting for equality.

Activist Lupe Anguiano reflects on a life spent fighting for equality.