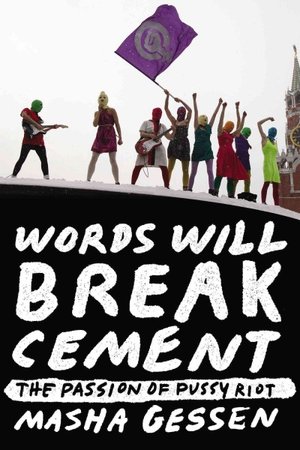

Journalist Masha Gessen wrote a well-received biography of Russian president Vladimir Putin two years ago. In her new book Words Will Break Cement, she profiles Pussy Riot, a Russian feminist punk activist group whose members have become the international faces of anti-Putin protest.

In recent years the group has won a global following—including the likes of Madonna and Paul McCartney—for their offbeat acts of civil disobedience against the Russian government. One of their best-known protests—a controversial “punk prayer” performance in a Moscow cathedral in 2012—eventually landed three of its members in jail. Gessen, a Russian American journalist and herself a critic of Putin, follows the personal histories of these three members: Nadezhda Tolokonnikova (Nadya), Maria Alyokhina, and Yekaterina Stanislavovna Samutsevich (Kat). Most of the book was culled from Gessen’s reporting from their trial and her correspondence with Nadya and Maria while they were in prison.

Nadya, we learn, grew up with a love for philosophy. One of her heroes was Anatoly Marchenko, a Soviet dissident who wrote about the experiences of political prisoners in Soviet camps. Bookish Maria long felt herself to be an outsider, and yet, as one of her friends put it, she also “had this idea that she would change the world.” Kat was trained as a computer engineer. Gessen describes her as cerebral, sometimes too much so: “Her word choice was always intentional, but she seemed unaware of images or associations that her words called forth in others, and as a result her speech often served to obscure rather than to illuminate.”

Before Pussy Riot, Nadya was involved with an art collective called Voina (roughly translated as “War”). Formed in 2007, the group used street art to criticize corrupt politicians, police, and clergy, staging colorfully named (if somewhat clumsily executed) protest pieces throughout Russia that involved a wide range of illegality: from vandalizing police vehicles (“F*** the FSB”), to stealing groceries while wearing priestly robes and a police officer’s hat (“Cop in a Priest’s Cassock”). After Voina split in 2009, the faction based in Moscow eventually became Pussy Riot.

What set Pussy Riot apart from their earlier incarnation was their deliberate strategy to steer clear of “Art with a Capital A,” Gessen writes:

Indeed, the fact that it was art should be concealed by a spirit of fun and mischief. Whatever they did should be easily understood, and if it was not, it should be simply explained. It should be as accessible as the Guerrilla Girls and as irreverent as Bikini Kill. If only Russia had something like these groups, or anything of Riot Grrrl culture, or, really, any legacy of twentieth‐century feminism in its cultural background! But it did not. They had to make it up.

Pussy Riot soon developed their own style of protest: donning multicolored balaclavas and playing loud punk rock. Other than that, they seemed to make it up as they went along—storming designer boutiques, practicing on playgrounds, climbing atop buses. Once, they unintentionally set a fashion show on fire, and later called it “Pussy Riot Burns Down Putin’s Glamour.” On another occasion, they performed in Red Square to protest the detainment of three gay activists.

Even after the three members were hauled into court for their “punk prayer” at a Moscow cathedral, they remained—poetically—defiant. Plodding in its first half, the book takes off once Gessen gets to the trial, a dramatic media event that crystallized many of the reasons that the young women have become an international phenomenon. In her closing statement, Nadya invoked a quote from the Soviet dissident novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: “So the word is more sincere than concrete? So the word is not a trifle? Then may noble people begin to grow, and their word will break cement.”

All three of the women were convicted and sentenced to two years in a penal colony. Kat’s sentence was later reduced on appeal. As for Nadya and Maria, Gessen writes, “forty seconds of lip-synching cost them around 660 days behind bars.”

Cornelius Fortune is a journalist whose work has appeared in the Advocate, Citizen Brooklyn, the Chicago Defender, Yahoo News, and other publications.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content