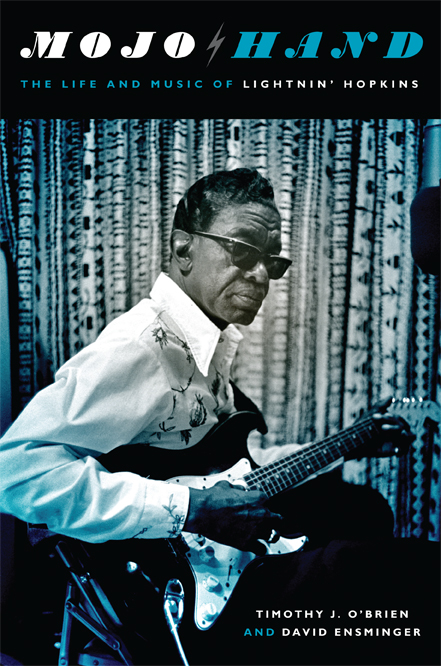

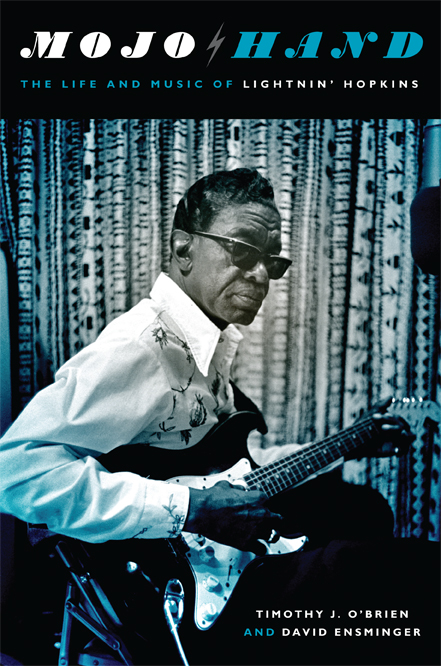

Blues legend Sam Hopkins — known as Lightnin’ Hopkins to his fans — influenced everyone from musical giants like Bob Dylan and John Coltrane to activists like Black Panther Party cofounder Bobby Seale. Long after his death, Rolling Stone named him one of the greatest guitarists of all time. Yet not much is known about him. Notoriously private, Hopkins fabricated and exaggerated details about his early life, preferring to keep his origins a mystery.

Mojo Hand, a new biography of Hopkins, details the obscure life and music of an iconoclastic bluesman who was the consummate musician’s musician, inspiring legions of artists across many genres. Born in 1911, Hopkins lived in rural Texas at a time when slavery was still fresh in the minds of those who would inherit its parting gift of Jim Crow. His grandfather, a slave, hanged himself to be free of its atrocities. His father was murdered when Hopkins was three, and his brother left home at fourteen to keep from avenging their father’s death. In his youth, Hopkins endured incidents of vicious racism, including the abusive treatment of white supervisors at the various plantations where he worked.

His was a family of poor sharecroppers with an affinity for music. Hopkins’s brothers, sister, and mother each played instruments, and Hopkins learned to play his older brother’s guitar. By age eight, he had made his own guitar with screen-door wire, and his prodigious skills kept him from having to inherit the “family business” of sharecropping.

Those skills also kept him from following convention. “He didn’t play with a clamp,” says drummer Robert Murphy, who worked with Hopkins. “He just played by ear, just like most of the old-time bluesmen. He wouldn’t pay much attention to whether it was an eight-bar blues or a twelve-bar blues, just as long as it fit what he was singing and doing.”

The biography captures quite well Hopkins’s aversion to conformity. From his playing style to the way he carried himself, Hopkins was a law unto himself, choosing to do things his way no matter what people said or thought of him. Long before Dylan was rejecting autograph seekers, or band members of Van Halen were making bizarre demands about M&Ms, Hopkins was known for his idiosyncrasies. He was a raconteur, a heavy drinker, and a fancy dresser. He would not record, or rerecord, if he didn’t feel like doing so. He refused to honor contracts that restricted him from working with other record companies at the same time, and would either change the name of a song or change his name to sidestep any lawsuits. He did not like venturing too far from his home base in Houston, and refused to fly, which made life difficult for those who worked with him, and made him hard to locate when there were deals that needed to happen. He did things his way, or not at all, with very few exceptions.

Dick Waterman, who booked gigs for Hopkins, points out that most blues artists came from rural areas. Though Hopkins was raised in Texas farm country, he stood out because he also had spent time in the city and been influenced by its culture. He carried himself as an “urban man” and played his blues not acoustic, but amplified with a pickup. As Waterman says:

He came from a very different place socially and musically. He was very cool. Some of the other [bluesmen] would be overly polite and respectful around white people, but Lightnin’ didn’t have any of that. Lightnin’ would just treat everyone the same, and if anything he carried himself with a sense of confidence and almost arrogance. He was Lightnin’ Hopkins.

Hopkins was also a loner. He would work with only one or two other bandmates, or just by himself. He preferred to be the focal point, and here he showed his nastier side. He would deliberately change the timing as soon as his band got used to a certain tempo or rhythm — in part to keep them from launching any ambitious solo efforts. Oftentimes, Hopkins would not rehearse, and the haphazard adjustments he made with every new performance made it nearly impossible to follow along while accompanying him.

Despite all these things — or, perhaps, because of them — Hopkins’s style is indelible. He made songs up impromptu, and hardly ever sang them the same way twice. His guitar playing was not easily mimicked: he changed it at whim and did not stick to any particular structure or chord style. He rambled through most of his concerts, telling stories that were at times incomprehensible, thanks to his drinking and thick Southern accent. And yet his performances thrilled his audiences.

Hopkins sang, in typical blues fashion, about women (short-haired ones, cheating ones, drunk ones). But his songs also had things to say about everything from work, to road trips, to politics. He often improvised lyrics, such as this freestyle take on astronaut John Glenn’s first orbit of the earth:

The main issue I had with Mojo Hand was the connection the authors imply between Hopkins’s illiteracy and his approach to business. Hopkins rarely signed contracts, and when he did he drew an “X” in place of his signature. He also preferred to be paid up front, in cash rather than royalties. Did Hopkins do these things just because he couldn’t read? The authors briefly mention the suspect business practices of music publishers back then, but they do not elaborate on how these practices often pushed musicians into destitution while the companies made money even long after their deaths. Royalties and publishing rights were rarely honored in those days, and many popular musicians were paid poverty wages for their work. These problems were rampant and well known in the blues and jazz worlds. Operating in a white-dominated industry, Hopkins clearly developed his own survival techniques.

The authors also could have dealt more with Hopkins’s influence on the generations of artists who came after him. Some of his fans included Ringo Starr, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Jimmie Vaughan, Johnny Winter, B.B. King, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Elvis Presley, and ZZ Top. How did Hopkins’s work inspire them?

Mojo Hand gives us some tantalizing details about a pioneering but private blues legend who, two decades after his death, remains an enigma. An alcoholic, an insatiable artist, and an understatedly temperamental man, Hopkins wound up becoming one of the greats, hailed by scholars as the “embodiment of the jazz-and-poetry spirit, representing its ancient form in the single creator whose words and music are one act.” In the end, though, this biography is just a sketch of the complex man Hopkins was, a troubled artist with a life that, just like his songs, cannot be fully translated to the printed page. Perhaps that’s what Hopkins would have preferred.

Olupero R. Aiyenimelo is a freelance writer, poet, and lyricist based in Los Angeles.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content