I have a remarkable story to tell you about forgiveness. A week ago, a man named Elwin Wilson died. A member of the Ku Klux Klan, Wilson was part of a group of white men who attacked two Freedom Riders in South Carolina in 1961. The victims, one white and one black, were traveling together throughout the South to protest Jim Crow segregation laws, and had stopped in a bus station in Rock Hill. When the two dared to step foot in a waiting area marked as “whites only,” Wilson and his group jumped them, leaving them bloodied.

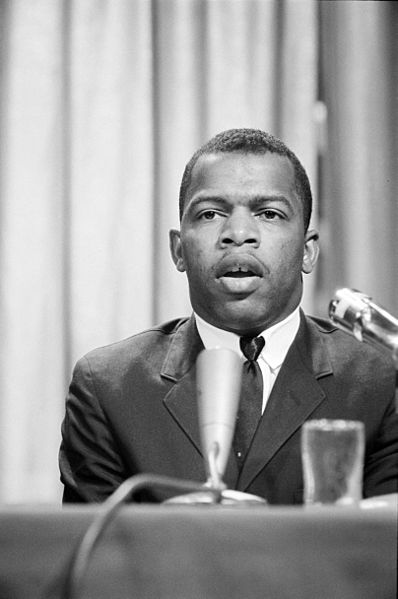

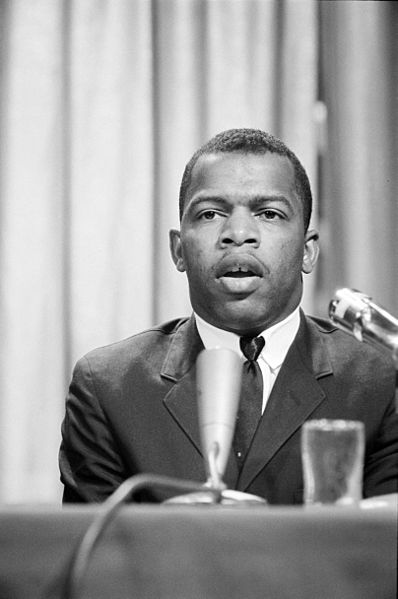

The two Freedom Riders, Albert Bigelow and John Lewis, refused to fight back and did not press charges. Lewis, a pacifist, later became the chair of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and a major leader in the civil rights movement. Decades later, he bears visible scars from having his skull fractured on “Bloody Sunday,” when Alabama state troopers beat civil rights protesters during the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches.

Four years ago, the story took an amazing turn. Wilson, then in his seventies, sought out the civil rights protesters he had harmed and asked for forgiveness. He learned that one of them was Lewis, now a Georgia congressman.

Lewis not only accepted Wilson’s apology — the first one, he noted, that any white supremacist had ever offered him — he also went on the road with his old nemesis. The two appeared on Oprah and accepted recognition from various organizations. Lewis said he wanted to use the occasion as an opportunity for racial reconciliation. It brought to mind words that the Reverend Martin Luther King once spoke of the day that “the lion and the lamb shall lie down together” — the one-time oppressor and one-time victim now hailing each other as “friend,” with the irony that their positions of power had been, in many ways, reversed.

At the end of his life, Wilson revealed a fundamental decency. If we had grown up in the same climate of hate, how many of us would have had the strength not just to overcome it, but to reach out to those we had wronged so many years ago? We should recognize men and women like Wilson who radically change for the better, who embrace love and reject hate.

But I also want to emphasize the courage it took for Lewis to accept that apology. Forgiving someone who not only beat you but rejected your very humanity takes tremendous character. It requires denying a very natural desire to hurt the person who hurt you, to inflict some of the pain that person inflicted on you, even if not through an equivalent act of violence.

Rather than taking his crimes with him to the grave, Wilson repented. Rather than indulge the impulse for vengeance, Lewis forgave. We could all learn from their example.

Ian Reifowitz Ian Reifowitz is the author of Obama’s America: A Transformative Vision of Our National Identity. Twitter: @IanReifowitz

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content