My romance with Bhutan began in February 2000, when I flew for the first time from Bangkok to Paro, the only airport town in Bhutan. The airport had no radar detection device. Planes could only land and take off in broad daylight, in good visibility. At the time, “planes” meant the two aircraft owned by Bhutan’s national airline, Druk Air. As we neared Bhutan, the arid landscape gradually gave way to layers of mountains looming grey and purple in the distance, becoming luxuriant with vibrant shades of green as the plane glided over them. Mountains and valleys interlocked with one another like fingers of hands clasped in prayer. I had the inkling I was about to experience something quite different from what the biggest cities and fanciest resorts of the first world could offer.

The day my husband Mike told me about his potential assignment to consult in Bhutan, I looked up the country on the Internet. Cradled in the foothills of the Himalayas, about the size of Switzerland, was the Kingdom of Bhutan, with India to the south, east, and west, and Tibet to the north. Further research told me the country had no constitution or political parties, no freedom of assembly, press, or religion. No church to attend, only Buddhist temples. No electricity in most parts of the country, and limited TV broadcasting even in places with electricity. No traffic lights anywhere, not even in its capital, Thimphu. No fast food restaurants. And little medicine except the indigenous kind.

There was a dress code: National dress was required to be worn in public. My findings were depressing enough to make Bhutan a curious — even fascinating — place to see.

As tourists in the first two weeks before Mike started work, we had a guide who took us from Paro to Thimphu and across the mountain pass Dochu La to Punakha, the winter home of the Central Monastic Body. We also journeyed eastward to the Bumthang district in central Bhutan. We even braved the narrow, nerve-racking, mountain-hugging roads south all the way to Phuentsholing, on the border of India. The fortress-like dzongs, or monasteries, intimidated and awed me. Houses decorated with auspicious, painted symbols of dragons, flowers, and wheels caught my fancy, while wooden phalluses — hung from roofs to ward against evil — initially rendered me speechless. Buddhist relic-filled chortens, prayer wheels big and small, and forests of prayer flags fluttering in the wind were spiritually uplifting.

But what really filled me with wonder was that every man, woman, and child looked happy.

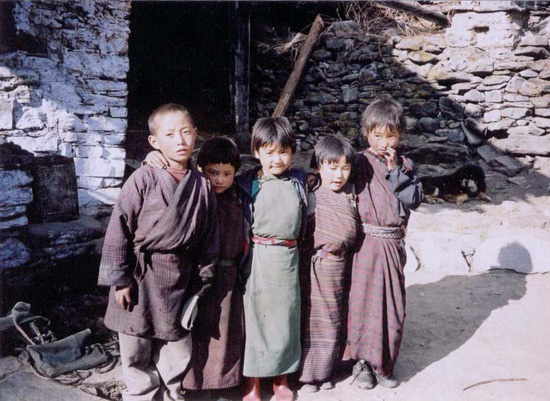

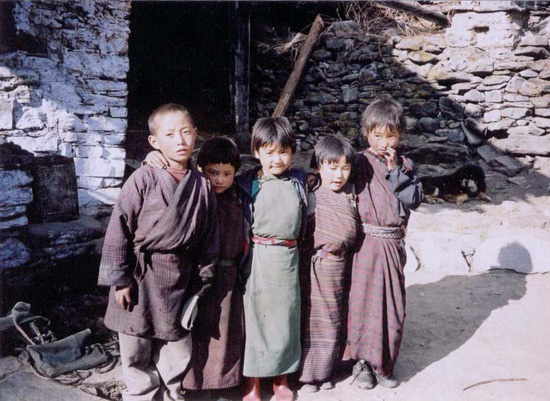

Happiness radiated from weather-beaten faces, with their windburned cheeks and smiles that showed teeth stained red from betel nut addiction. It was quite obvious that happiness in Bhutan was not born of material wealth and comfort, for those were lacking everywhere I looked. The Bhutanese people as a whole might be poor by Western standards, but they are not destitute. Begging and unwelcomed soliciting are not in the Bhutanese vocabulary. While tourists to many countries would have to pay to get a picture taken with a local outfitted in his or her national dress, I got all my pictures taken with Bhutanese men in ghos and women in kiras for free, for my payment often came in the form of letting adults pore over my Lonely Planet Bhutan or showing children the magic of my binoculars. What a breath of fresh air. The children might look shabby, with snotty faces and dirt-encrusted fingernails, but they all had school and parents who provided for them.

And they all looked happy.

A highlight of that first trip was a night in a farmhouse in a small hamlet during our Bumthang Cultural Trek. That evening, we shared a meal with the family, comprising a couple and their two sons. We sat on the floor around the bukhari, or wood-burning stove, in a kitchen surrounded by soot-blackened walls. The room was dimly lit with a low-wattage bulb, which our host proudly told us was fed by electricity generated by a solar panel on the roof. We dined on buckwheat pancakes, yak stew and curries, and lots of chilies, which Mike and I politely declined. Arra, a strong wheat- or rice-distilled drink, was poured, warming the body and the spirit.

In spite of the dark and drab surroundings of the interior, it did not take much to feel the contagious effect of happiness. That night, Mike and I were given the best room in the house in which to sleep: the altar room, reserved for the deities and VIP guests. In the darkness of the room, lit only by a flickering butter lamp on the altar, surrounded by statuettes of Buddhist saints and thangkas depicting deities, I was not afraid. Mike fell asleep as soon as his head hit the mattressed floor, but I stayed awake for a long while, thankful for the opportunity to be sharing in the happiness of an extraordinary nation.

On my second visit to Bhutan, in 2002, I went to the public library in Thimphu and picked up a copy of Kuensel, the national weekly. “Chorten vandal sentenced to life,” the headline read. Also on the same page: “Eight HIV cases detected in Bhutan.”

Little international news made it into the paper. Neither did anything critical of government policies. Surely there must be some souls unhappy with contentious issues even in the most fairytale paradise on earth?

“They are careful of what they print, aren’t they?” I remarked to a man reading nearby.

He gave me a curious look, and said, “Yes, it’s a pretty good paper.”

Up until 2008, the country had no constitution. But for 100 years, the Bhutanese people had placed their faith in the king and his benevolent, if absolute, governance. Peace and harmony reigned in this kingdom which, to the developed world, might seem deprived of the fundamental rights of democracy and freedom. On my visits to Bhutan, I have observed that the Bhutanese are intrinsically happy, if happiness could be summed up to trust in their beloved king and his government, contentment with their way of life, faith in their religious beliefs, harmony with their environment, peace with all sentient beings, and the highest regard for the cultural and spiritual traditions of their country.

With a new king and Bhutan’s first constitution, the kingdom has entered a new era, one of democratic beginnings. The Internet has become accessible, more programs are broadcast on television, and new hotels are being erected.

It’s progress by Western standards.

But what about happiness?

Elsie Sze is the author of the novel Hui Gui: A Chinese Story, which spans from the war torn China years of the 1930s to the 1997 handover of Hong Kong. Her forthcoming novel, Heart of the Buddha, is about Bhutan.

Additional reading:

Books offer clues to finding happiness in tough economy

Substantiating GNH

Lessons in Gross National Happiness

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content