A few years ago, I took a personality test. A hundred “yes” or “no” questions, such as Do you require structure (yes), Do you keep your thoughts to yourself (no), Would you like some level of fame (duh). The last question was fill-in-the-blank: Describe your self-image. I got stuck on that one. How can you sum it up in a single word? Writer, teacher, Democrat, Chicagoan, and on and on. How you fit all that into an inch-long fill-in-the-blank is beyond me.

But then I moved to the Czech Republic.

I teach in the fiction department at Columbia College in Chicago, and I am a faculty member in its study abroad program in Prague. I teach the works of Franz Kafka, drink wine in cafés, sit around being obnoxiously literary, and yes, it’s just as great as everyone says — so much so that in 2004, I decided to stay. I went on sabbatical for the fall semester, sold all my stuff, and stashed my car at Gramma’s. My boyfriend, Christopher, and I rented a furnished flat on Belgitzka in Namesti Miru, a primarily expatriate community. Our landlords were Yugoslav, a French couple lived on the second floor, and the only decent Mexican restaurant in the city was across the street. Had I, at that time, been asked to fill in my self-image, it would have been easy: I was an American.

Prague is a true fairytale, all castles and churches and curving cobblestone streets—hands down the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen. But as you know, beauty attracts, and every summer, tourists overrun the city. Many are American, and they — ahem — we are easy to spot.

I’d be writing in a café, sitting next to a table of girls. I could tell they were American because of 1) the accent and 2) the pants. Great fuckin’ pants, those American girls, with their credit cards, full-on makeup, and loud voices: “Are you ser-ious?” They’d flip through entertainment guides, go to the Roxy later, and talk about Doug calling last night from Ohio. “He’s, like, coming to visit in November and I, like, cannot wait!” they’d say and then reapply their high-end lip gloss — always MAC or Chanel, those American girls!

I’ll pause to marvel at my own hypocrisy, sitting here in my Ralph Lauren. How am I different from those girls? Certainly I can answer that question, but what about the Czechs? To them, my image was the same as those girls: We were American.

I assured her I was.

“No, Americans — they talk like this,” she said, and then, in pitch-perfect Valley Girl: “What you mean I must eat potato! You know how much the carb in potato?”

Looking back on it, I should have been flattered that she didn’t think I sounded “American.” In the moment, though, I was drunk on Frankovka, and all I did was laugh.

“You eat here long time,” she said. “Why you in Czech Republic?”

I told her I was teaching Kafka, the writer whose picture happens to adorn every T-shirt and coffee mug in the city.

“Io, Kafka. He was bug,” she said, referring to his story The Metamorphosis, where Gregor Samsa wakes up as a giant cockroach. “You smoke the water pipe? Tomorrow you come my house. We smoke water pipe. Okay? Bye bye.”

This was Marketa, our first Czech friend.

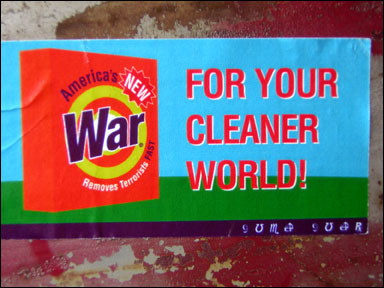

We needed one. The war in Iraq was going strong, and the campaign for the U.S. presidential election was well under way. Foreign anti-American sentiment was high, and some of my students had sewn Canadian patches onto their backpacks as a precaution.

We met Marketa in her studio apartment. A mattress sat on the floor. The table was a piece of plywood laid across a crate. Candles were everywhere, and she pointed out the different countries where she’d bought them: Tunisia, Morocco, France, and Croatia.

“One time, I wait on your president,” she told us, pouring wine into teacups. “He was here for party, and I am catering. We must keep our arms like this,” she clasped her arms at her sides, “so his soldiers can see our hands.”

“His soldiers?”

“Secret Service,” Christopher said.

“Yes, and he just sit there all night with look on his face.” She set her expression in a creepy joker-type grin. “He is really … what’s the word …

She flipped through the Czech-English dictionary. “No, here,” she said. “He is … ray-deck-oo-lush, no, LUS, ray-deck —”

“Ridiculous.”

“Rideck … ah, my mouth does not do this word. Here, there are more.” She looked back at the dictionary. “Laughable. He is laughable, yes?”

I wasn’t sure how to respond. Back in Chicago, among my liberal friends, I would’ve said the obvious: “Yes, he is laughable.” But sitting in Marketa’s living room so far from home, an unfamiliar confusion grew in the pit of my stomach. How could I feel both pride for my country and disdain for my president?

Marketa interrupted my thoughts. “There is election soon in your country,” she said. “For which do you vote?”

“Kerry,” I told her.

“Good,” she said. “Now we may be friends.”

Our friendship with Marketa had two main parts:

1) She took care of us. When Christopher and I got food poisoning, it was Marketa who explained to the pharmacist what we needed. We’d get text messages that read my Megane, tomorrow is state holiday so the stores they will be closed so shop today, please.

2) We dispelled her image of what “America” was.

“Chicago is dangerous,” Marketa said over beer and foosball. “There are gangsters.

“There are gangs,” Christopher told her. “They’re not like Al Capone.”

“What are gangs?” she asked.

This happened over and over, these words in the English language that I’ve never had to explain because I’ve always lived them. But, lived them how? What is a white, middle-class girl doing explaining Chicago gang culture?

Gang culture is a part of America. So are farming, and Republicans, and Xbox, and factory work, and millionaire CEOs, and all the things I can’t understand myself, let alone explain.

That really came to a head after the election. Our Czech friends would ask, “Why do the American people vote for this man?” It forced me to think outside my shock, anger, and political affiliations. I’d say, “There are some people in my country who feel differently,” and in trying to explain how “those other people” felt, I’d like to think I understood a little more about my country.

On the day after the election, Marketa sent us a text message: Oh no! I would like to cry! Shit! I don’t understand people who want to have so bad president! Don’t be sad please, I am sorry about your bad president and I still like you.

While she still liked us, many others just saw us as Americans. On the day Bush asked the Czech government for soldiers to replace Americans in Iraq, Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 came out in Eastern Europe. Christopher and I attended a post-screening discussion, and it became very clear what Czechs thought of our government. I felt more and more confused and disconnected: How could I be homesick for a place that was pissing me off so much?

Shortly before we returned to Chicago, Christopher and I were walking through Old Town Square, warm from the wine we had at dinner. It was a beautiful, cool night. Every A-frame and tower-top lit the sky like a theater set. In the center of the square was a huge crowd, at least 100 people, all of them singing “Another Day in Paradise.” In the middle of it all was one guy and a guitar, which he played badly, but it didn’t matter. What mattered was the song, a single, stupid song that every person — whatever their nationality — knows the words to, and in that moment we were all together, all of us singing (even me, and I hate Phil Collins!). There were little kids, and older people, and couples holding hands. The woman next to me was wearing a sari, and she smiled, and we sang, and I wasn’t confused or disconnected that night. I was part of something greater.

The day before we left, Marketa gave me one of her candles. “Don’t worry about being American,” she told me. “It is more important that you are my friend.”

If someone were to ask me now what my self-image is, I’d still say Writer. Teacher. Democrat. I’d also say American. What I’ve got to come to terms with is what that means for me. But if there’s room for only one word to fill in the blank, I’d put: friend.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content