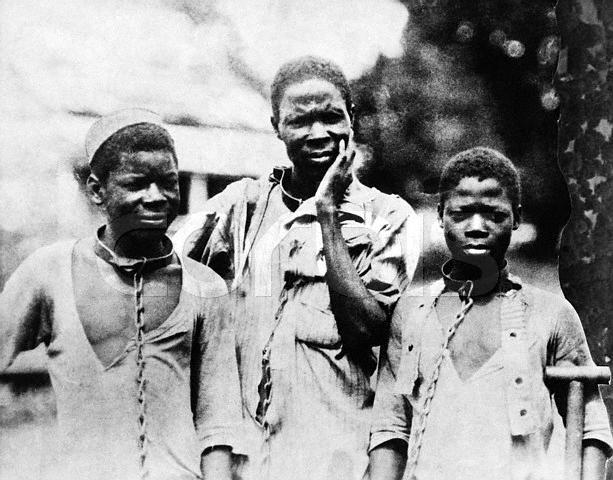

According to Richard Re, a senior editor at the Harvard International Review, "Conservative estimates indicate that at least 27 million people, in places as diverse as Nigeria, Indonesia, and Brazil, live in conditions of forced bondage."

Some estimates place that figure at 10 times the number, more than a quarter of a billion people. To put that in perspective, Re writes, "It is believed that 13 million slaves were taken from Africa through the trans-Atlantic slave trade that ended in the 19th century."

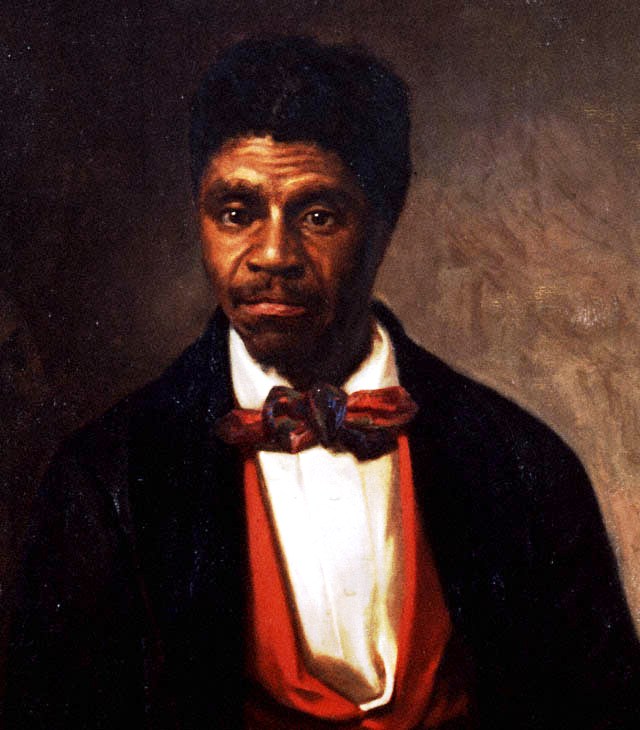

When Dred Scott and his wife Harriet arrived in St. Louis, Missouri, in the spring of 1846, they came as refugees in their own land, and they must have been overwhelmed by the willingness of white St. Louisans to accept them as free Americans.

The Scotts, after all, had been the property of white America their entire lives. Moved from one state to another by their owner, Dr. John Emerson – a military physician – the Scotts lived for many years in Illinois and Wisconsin, two states where slavery was not institutionalized.

The Scotts, after all, had been the property of white America their entire lives. Moved from one state to another by their owner, Dr. John Emerson – a military physician – the Scotts lived for many years in Illinois and Wisconsin, two states where slavery was not institutionalized.

Following the death of Emerson, Dred and Harriet Scott returned to Missouri where, with the help of white sympathizers, they applied through the courts to obtain their freedom. Three years later, in 1850, a jury decided the Scotts should be freed under the Missouri doctrine of "once free, always free."

That, however, was not to be the case; after a torturous, eleven-year court battle, the U.S Supreme Court ruled the following in 1847:

• Any person descended from black Africans, whether slave or free, is not a citizen of the United States, according to the U.S. Constitution.

• The Ordinance of 1787 could not confer freedom or citizenship within the Northwest Territory to black people.

• The provisions of the Act of 1820, known as the Missouri Compromise, were voided as a legislative act because the act exceeded the powers of Congress, insofar as it attempted to exclude slavery and impart freedom and citizenship to black people in the northern part of the Louisiana cession.

The decision shook the entire nation when it was announced, and its aftershocks reverberated through the end of the Civil War.

March 2007 marks the 150th anniversary of the Supreme Court's momentous Dred Scott decision, which denied full American citizenship to African Americans and gave legal sanction to a racial hierarchy that would undermine the most basic principles of American justice.

In honor of this landmark case, Washington University will host a conference, "The Dred Scott Case and Its Legacy: Race, Law, and the Struggle for Equality," from March 1-3.

Speaking for the event, David Konig, Ph.D., professor of law in the School of Law and of history and African & African American studies at Washington University in St. Louis, says "This anniversary will undoubtedly be a moment of deep national reflection on enduring issues of race and justice and is a reminder of the persistence of so-called 'badges of slavery' making the 13th Amendment an unfulfilled promise, and the 14th and 15th Amendments incomplete."

The event, which is free and open to the public, will bring together leading law, history, and culture experts, as well as judges and descendents of Dred and Harriet Scott.

"This symposium, devoted to the continuing legacy of the Scotts' struggle, hopes to examine the legal background of the case and its legacy, both of which involve the uncertain and problematic role of the law in addressing fundamental questions of justice, racism, and inequality," says Konig.

"It will inquire into the legal strategies of black and white abolitionists before 1857, as well as the efforts of civil rights attorneys, to make meaningful the full legal citizenship that the decision denied. Its concerns will, therefore, be contemporary as well as historical, combining the perspectives of many disciplines to examine the historical roots of legal inequality and to understand the power of its persistence."

"The Dred Scott case isn't a ghost," Konig says. "We haven't outgrown implicit embedded cultural forces from Dred Scott. They act on the law, they penetrate the law, and they come through the law to enforce stereotypes. The current immigration debate is just one example."

John Baugh, Ph.D., the director of African & African American studies in Arts & Sciences and Washington University's Margaret Bush Wilson Professor, notes that the Scott trial has global relevance to anyone concerned with equality.

"It far exceeds the experience of slave descendants in the United States, although it is an iconic example of the historical injustice suffered by U.S. slaves and their descendants," he says.

"The Scott case confirmed that America was once a nation where racial discrimination, supported by legal statute, defied the doctrine of equal opportunity and justice for all that has been the beacon of American liberty to those whose ancestors came to America of their own volition," says Baugh. "Slaves were denied access to justice, and the Scott decision attempted to codify racial inequality, albeit in direct defiance of the colorblind vision that Dr. King expressed in his unfulfilled dream of American racial equality."

Resources:

Washington University Symposium March 1-3, 2007

Full text of Supreme Court Dred Scott decision

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content