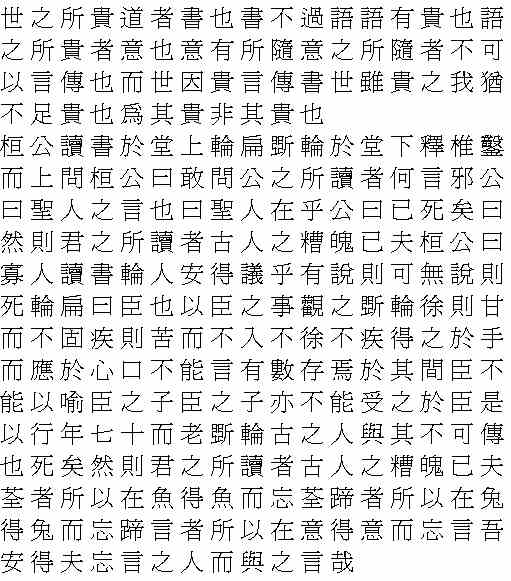

Books are no better than talking. In talking there is something precious: the intention. Intention tunes to something, but what it tunes to cannot be passed down through words. Yet, because they treasure words, people transmit books. Let them treasure it! For me there is nothing worth treasuring there. What they value in words is not what they are precious for.

…

Duke Huan was reading a book in the hall. Wheelwright P’ien was carving a wheel nearby. Putting down his chisel, the wheelwright went up to the duke: “May I ask what words my lord is reading?”

“The words of a wise man.”

“Is the wise man alive?”

“He is dead.”

“Then my lord is only reading the dregs of a dead man.”

“How do you, a wheelwright, dare to pass judgments when your master is reading? If you can justify yourself, good for you; if not, you die!”

“I look at it from the point of view of my own work. When I pound the chisel too softly, it does not hold on to the wood; when I pound too hard, it does not incise. Not too soft, not too hard—my hands find the way, and the mind follows through, but the mouth cannot explain it. There is a measure in it I cannot relate to my son, and my son cannot learn from me. I have been doing this for seventy years, growing old carving wheels. The men of the past are dead, along with what they could not pass down. Thus all my lord is reading are the dregs of dead men.”

…

The point of the net is the fish. When you get the fish, you can forget the net.

The point of the snare is the hare. When you get the hare, you can forget the snare.

The point of the words is the intention. When you get the intention, you can forget the words.

Where do I find a man who has forgotten words, so that I can have a word with him?

About the piece: Anecdotes like this one circulated through China’s central states for centuries, attributed to the semifictional character Chuang Chou. Linked by a playful poetic language, they poked fun at conventional wisdom. They were later collated into the definitive book of Master Chuang by the Taoist scholar Kuo Hsiang (who died in the forty-seventh year of the Western Chin, i.e., 312 AD).

Jan Vihan Jan Vihan is a contributing writer for In The Fray.

- Follow us on Twitter: @inthefray

- Comment on stories or like us on Facebook

- Subscribe to our free email newsletter

- Send us your writing, photography, or artwork

- Republish our Creative Commons-licensed content